![]()

Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s musical about marriage and the choice to remain single gets a thoroughly modern staging

Terry Teachout on June 30, 2012

Sooner or later, every play becomes a history play, a time capsule whose carefully preserved contents show us something of what life was like at a particular moment in the past. Some plays, however, tell us far more than others about such moments. One of them is “Company,” the 1970 musical in which Stephen Sondheim and George Furth described what it was like to be a member of the urban bourgeoisie at the moment when America was becoming a country where marriage for life is not a normal destiny but an increasingly remote possibility. Twenty years ago I thought that “Company” was a period piece. Today it seems prophetic, a hardheaded comedy about the way we live and love now—and its hardheadedness helps to explain why it doesn’t get done as often as it should.

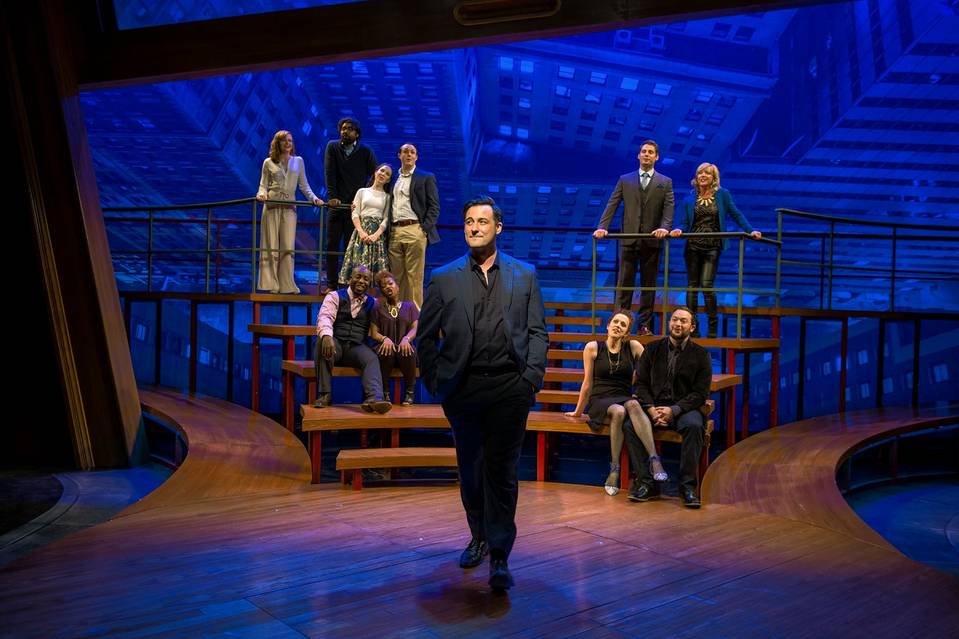

It figures, then, that first-class revivals of “Company” should be thin on the ground. I’ve reviewed only two, on Broadway in 2006 and at Pennsylvania’s Bucks County Playhouse last summer. Now there’s a third: William Brown, one of Chicago’s top directors, has given us a small-scale, contemporary-flavored “Company” (everyone uses cellphones) that is the most dramatically persuasive version I’ve seen to date. It’s the first musical to be mounted on Writers Theatre’s new 250-seat main stage, and it takes full advantage of that handsome space. Indeed, the real “star” of the show is Todd Rosenthal, the set designer. Best known in New York for “August: Osage County,” he has concocted a multitiered performing space that shows you how the complex narrative structure of “Company” works. Everything about this production is wholly satisfying, but it’s Mr. Rosenthal’s set that makes the pieces fit together so tightly.

If you’ve never seen “Company,” the setting is—or seems to be—a surprise birthday party for Bobby (Thom Miller), a New Yorker who’s just turned 35 and whose married friends wonder why he won’t take the plunge himself. The answer is that he’s desperately afraid of commitment, in part because he can see only the flaws in their marriages. (As one of them says in a toast, “May this day bring you fame, fortune and your first wife.”) He longs instead for a relationship with a woman to whom he can be close, but not too close: “You promise whatever you like, / I’ll never collect.” No sooner does the party get going than “Company” turns into a series of sketches, five of which portray the married lives of Bobby’s friends and three of which introduce us to the women whom he’s dating. Some of the songs (“Getting Married Today,” “The Ladies Who Lunch”) take place “inside” the sketches, while others (“You Could Drive a Person Crazy”) comment on the unfolding plot. At length we return to the party—and discover that what we saw when the curtain went up didn’t really happen.

Sound complicated? That’s where the set comes in. The back wall is a giant window that looks down from a high-rise apartment to the street below. In front of it is an asymmetrically arranged group of stepped platforms and bleachers that descend to the thrust stage, on which is placed a circular ministage that’s about the size of a tiny Manhattan living room. The songs and sketches about married life are performed on the ministage, while the songs that comment on the sketches are (mostly) sung from the platforms.

Mr. Brown and Brock Clawson, the choreographer, use this space flexibly but logically, the result being that you know at all times where you are and what you’re seeing. This lets you concentrate on the show itself, and on the acting of the 14-person cast. Everyone keeps it simple—the performances are all rendered in bright primary colors—and Mr. Sondheim’s score is both beautifully sung and played with cool clarity by the seven-piece pit band. Yet there’s no lack of passion, least of all from Mr. Miller, who seems at first glance like an affable lightweight but soon reveals himself to be full of longing and doubt. Anyone tempted to parrot the whiskery cliché that Mr. Sondheim is cynical about marriage need only listen to Mr. Miller sing “Marry Me a Little” to learn otherwise. As for Bobby’s friends and girlfriends, I was especially struck by Jess Godwin, Allison Hendrix, Blair Robertson and Alexis J. Rogers, but the whole ensemble deserves unstinting praise.

The virtues of Mr. Sondheim’s songs are a known quantity: “Company” put him at the center of the map of American theater, and it remains one of his signal achievements. Furth’s book too often gets short shrift by comparison, but Mr. Brown’s staging makes it surpassingly clear that the sketches are as good as the score. I doubt you’ll soon see a stronger, more sympathetic production of “Company,” or one that moves you more deeply.